Enhance your Impact

5 things you need to get right if you want to successfully engage with publics and stakeholders for impact

Conventional wisdom tells us that researchers that involve stakeholders and publics heavily in their research are more likely to deliver impact. Arnstein’s famous “ladder of participation” suggests that anything less than citizen power is tokenistic and manipulative, but new research from an international team (cited below) suggests that there are a number of situations where you might want to purposefully opt for a less participatory approach.

The researchers cite examples of highly co-productive processes that have gone wrong, and point to examples from the UK’s Research Excellence Framework impact case study database where lower levels of participation led to major impacts. Rather than always aiming for as much participation as possible, they argue that researchers should select the type of participation that is most relevant for achieving the sorts of impacts they want to see, in the specific contexts they are working in. They identify 4 types of participation, based on who initiates and leads the process (researchers or stakeholders/publics) and how closely researchers work together with stakeholders and publics:

1.

Top-down, one-way communication and/or consultation: participation is initiated and led from the top-down by researchers who consult publics and stakeholders (but retain decision-making power) or simply communicate messages and impacts from the research to them. This may be appropriate where an impact has already arisen from the research and cannot be changed, but needs to be communicated to those affected

2.

Top-down, one-way communication and/or consultation: participation is initiated and led from the top-down by researchers with decision-making power who engage publics and stakeholders in two-way discussion about the research, enabling the researcher to better understand and explore suggestions with stakeholders before delivering impacts. A more co-productive approach would typically include deliberation, but the impact would be jointly developed and owned by both the researchers and stakeholders/publics. Despite this, it would still be the responsibility of the research team to ensure that decisions are implemented on the ground to generate impacts by researchers who consult publics and stakeholders (but retain decision-making power) or simply communicate messages and impacts from the research to them. This may be appropriate where an impact has already arisen from the research and cannot be changed, but needs to be communicated to those affected

3.

Bottom-up one-way communication and/or consultation: participation is initiated and led by stakeholders and/or publics, communicating with researchers, often via grassroots networks and social media, to persuade them to open the research process to scrutiny and engagement. Those leading the process may consult with other publics and stakeholders to better understand and represent their views and demonstrate buy-in and support, and so increase their capacity to influence the research

Bottom-up deliberation and/or co-production: participation is initiated and led by stakeholders and/or publics who engage in two-way discussion with other relevant publics and stakeholders to generate impacts. The impact may be achieved by a single stakeholders/publics or a small group thereof based on knowledge gained through deliberation, or the impact may be co-produced, owned and implemented by the whole group

4.

The team argue that the key factors determining whether or not researchers are able to deliver impacts through stakeholder and public engagement are: how challenging the context is for the researchers to work with stakeholders/publics and generate impacts; how well the engagement process is designed; how effectively power dynamics between the research team and different stakeholders/publics is managed; and whether the research team adapted their engagement to relevant time and spatial scales.

Based on these factors, the research identified 5 things you need to get right if you want to successfully engage with publics and stakeholders for impact:

Take time to fully understand local context to determine the appropriate type of participatory approach and adapt its design to the context

1.

2.

Get all affected parties involved in dialogue as soon as possible, to develop shared goals and co-produce outcomes based on the most relevant sources of knowledge

Manage power dynamics, so every participant’s contribution is valued and all have an equal opportunity to contribute

3.

4.

Match the length and frequency of engagement to the goals of the process, recognising that changes in deeply held values (that may be at the root of a conflict) are likely to take longer than changes in preferences

5.

Match the representation of stakeholder interests and decision-making power to the spatial scale of the issues being considered (e.g. a local committee to site a park bench shouldn’t be setting national policy priorities but there’s no point in organising a national process to decide where to put the bench).

Reed MS, Vella S, Sidoli del Ceno J, Neumann RK, de Vente J, Challies E, Frewer L, van Delden H (in press) A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public participation in environmental management work? Restoration Ecology

Since the advent of PowerPoint, researchers have been doing visual design on an almost daily basis, usually not very well. Most of us will have felt the effect of poor design: the sharp intake of breath when you turn a page to find the World’s Most Complicated Diagram, which would probably have been highly informative had it not intimidated you into turning the page again so quickly; the desperate desire to do something useful rather than experience Slow Death by PowerPoint slides packed full of tiny text and no pictures; or the urge to RUN AWAY from the 1990s personal website with flashing coloured buttons and star GIFs that make you feel like you’re on the deck of the Starship Enterprise.

To be credible, your audience needs to perceive that you are believable, according to Daniel O’Keefe’s 2002 book, Persuasion: theory and research”. To be believable, you need to be perceived as a credible source with a credible message. Most researchers assume that it is self-evident that they are a credible source and only focus on their message. In doing so, they may unwittingly undermine the credibility of their message in the eyes of their audience.

In 1952, two Yale University psychologists, Hovland and Weiss, demonstrated how the persuasiveness of a message is influenced by its source. Their experiment, using an Army orientation film, showed that exactly the same message, communicated by two different sources (one presented as trustworthy, and the other presented as untrustworthy), was perceived by participants to have significantly different levels of credibility. A body of research has built on this, showing that there are three dimensions that determine the perceived credibility of a source:

Expertise is the extent to which the source is perceived as being knowledgeable, experienced, authoritative and skilled;

-

Trustworthiness is the perceived integrity of the source, and may be influenced by a researcher’s institutional affiliation in addition to their personal characteristics and message. This has been shown by many studies to be the most influential of the three dimensions; and

-

Dynamism refers to the way that the message is delivered. In a spoken context, this refers to the charisma, clarity and confidence with which the message is delivered. In written form, this is about concise clarity, and visually, this is about the use of design to communicate energy and confidence, for example through the use of colour, font and imagery.

If we have done original, significant and robust research, and know that we have expertise in our subject area, then we’ve already ticked the first box. However, we cannot assume that our audience will automatically then perceive us to be trustworthy or dynamic. Audiences will make subjective and often unconscious decisions about the most important of these three dimensions, trustworthiness, based on the look and feel of your message. They will do this in a matter of seconds, and if the judgment is not favourable, it will be very difficult to retain or regain their attention.

Researchers typically pay little attention to the visual information that audiences use to judge their trustworthiness. Admittedly, researchers can probably get away with wearing less professional attire than most professions, but particularly when speaking to stakeholders and publics, looking scruffy or like you’re on holiday may detract from your perceived trustworthiness.

It is harder to get away with amateurish design if you want to be perceived as a credible source with a credible message. This is a deeply unpopular message with many researchers who (rightly) argue that they should be focusing on excellent research, rather than wasting time dressing their work up with nice pictures. Clearly our focus as researchers should be on the quality of our research, first and foremost. But if you have done world-leading research, giving a little bit of thought to design could make your hard work travel significantly further.

Do your design skills undermine your credibility and impact?

Take this example: which of these research project websites do you think you would be more likely to explore? The Project Elgon website was made by a researcher with no design expertise. The Peatland Tipping Points project website was designed by Anna Sutherland, Fast Track Impact’s In-house designer, in collaboration with the same researcher, Fast Track Impact’s Mark Reed.

The chances are, that when you instinctively gravitated towards the professionally designed website, you made a number of sub-conscious decisions about the credibility of the site based on its colour scheme, fonts and images.

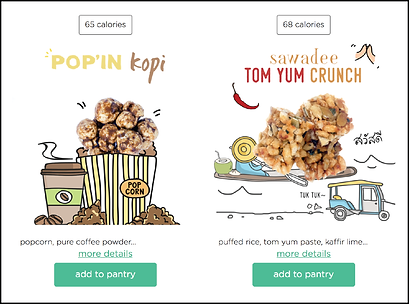

Alternatively, compare these two

competing websites making health claims

about snacks.

The majority of people judge the website with hand-drawn images ("Pop'in Kopi" and "Sawadee Tom Yum Crunch") to be more attractive, informative and reputable, partly due to its more appealing pictures, fonts, and colors.

These first impressions take seconds to form, and significantly influence people’s decisions to continue interacting with your work or move on. If you are trying to appeal to stakeholders and publics, this could make or break your ability to achieve impact. Although design is only one component of website credibility, poor design can very quickly turn people off your work and make it harder to engage effectively with them online.

When it comes to making a credible website or presentation, the small things matter. Font may seem like a small thing, but we immediately feel the gravity or lack of it when we contrast Times New Roman with Comic Sans. More subtlety, research has shown that project logos with parts of characters intentionally blanked out reduce perceptions of trustworthiness but increase perceptions of innovativeness.

In this example (see below), Paul Lowry and colleagues, writing in International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction in 2014, gave 220 people a range of websites with the same content but more or less credible logo and website design:

Across all the websites they tested, they found that professionally designed websites with credible logos were most trusted. Here is one of the hypothetical websites they made – which version would you trust?

If you chose the image with the lizard logo, you would be agreeing with the study participants. Whether we like it or not, design matters if we want our research to travel and have impact.

Fortunately it is easier and cheaper than ever before to add professional design to our websites and presentations. There are numerous website design platforms with customizable templates for you to make your own website. If you don’t have time to do that, or want something more unique and tailored to the specific audiences for your research, then it may be more achievable than you think to work with a professional designer. Services like Fast Track Impact’s Design for Impact give you access to the full professional design process for a fraction of the cost you would normally pay for professional design.

Don’t just design your next website or talk to be informative; design it to have impact.

Find out about our Design for Impact service.

Lowry, P.B., Wilson, D.W. and Haig, W.L., 2014. A picture is worth a thousand words: Source credibility theory applied to logo and website design for heightened credibility and consumer trust. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 30: 63-93.

The two most common reasons why stakeholders may not be interested in your research are that:

-

Your research is too narrow, niche or specific to be of significant interest; or

-

Your research does not fit with the ideology of the decision-makers.

If your research is too narrow, then you probably need to broaden your work. You will need to do some investigation into the issues that are of particular relevance in your area, so that you strategically broaden the coverage of your work to issues that are pertinent to the interests of the relevant audience. There are two ways you can do this:

Overcoming an ideological clash is typically more difficult. This is most common in policy circles, but can happen elsewhere too. In policy settings, the most common first solution is to approach an opposition party that has a good chance of winning power in the next election, and getting evidence-based policy ideas into their next manifesto. Some researchers take a more adversarial approach, creating alliances with pressure groups that are opposing the Government, businesses or other organisations that will listen to the findings of their research.

An alternative approach is to take the research to another country that is experiencing comparable issues. In the UK, that could be England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland, or it could be a country on the other side of the world. In some cases, you may have to create a collaboration with a research

team from that country first to generate evidence with them that builds on your former work to have the credibility required to be taken seriously by decision-makers in that country.

If you are really having problems and are prepared to invest some serious time and energy into this, then there is another option available to you. You can make a “pincer” movement from the bottom up and the top down to communicate evidence from your research to the people who can affect change within the organization that is not listening to your work. First, working from the bottom up, find people lower down the organizational hierarchy who you can help, based on your research and other capabilities, focusing on what they need and how you can make their jobs easier, but not hiding the nature of the work you are doing, and the fact that it may be ideologically contentious for the organization. Gradually, as you build trust, find out who are the more senior, middle-ranked people in the organization with some decision-making power and access to the main decision-makers at the top of the hierarchy. If an internal colleague can introduce you to them, based on a long-term relationship of trust built on useful work you have done to help them, there is a good chance that the new colleague will trust you by proxy. As a result, you are much more likely to be given the opportunity to talk about your research than you would otherwise have. Also, as a result of the work you have done already with your colleagues, you will have a much better idea where the ideological sensitivities lie, and how you might be able to frame your work in a way that is less contentious.

At the same time, the second half of the “pincer” movement is to work from the top down. This is much harder for most researchers to do themselves, and may require help from an intermediary who already has the ear of the decision-maker. This means that the first step is to find out who has access to the decision-maker, and who the decision-maker goes to for new ideas and advice. Depending on who these people are, it may be possible to reach them and communicate your research in ways that will resonate with them. They are then much more likely to be able to frame your work in a way that is ideologically palatable to the decision-maker. If they then seek advice from their team or ask their team to implement a decision based on your research, they are not going to be greeted with skepticism or concerns from their staff, because they already know about and understand your evidence.

Help! My stakeholders aren't interested in my research

1.

You can broaden your work yourself, either by asking new research questions or drawing of the evidence of others publishing in the area; or

2.

You can team up with other researchers working in your field to create a collaborative impact initiative, in which you create joint policy briefs and offers of help to industry, Third Sector and others. This latter approach tends to work best if there are others within your institution that you can team up with, to avoid issues of competition.

No matter how terrified and unconfident you may feel, it is possible with a few tips and some practice, to present your research with real impact. Honing your presentation skills can help you make more of an impact on your academic peers as well as opening up opportunities for non-academic impact. Bad presentation skills can squander opportunities for impact and alienate the very people who might have benefited from our work.

Some researchers make talking to businesses and policy-makers look easy. The rest of us look on in awe, desperately wondering how we could create such succinct and relevant messages based on our research. Many of us conclude that it is “easy for people who do that sort of research”. However, most of these people started in a similar position to us; they just focused for a while on an aspect of their research that had the potential to be useful to that audience, and spent some time thinking about how they could communicate it powerfully.

Researchers have to do public speaking on a regular basis, but most of us are never given any proper training. There is no replacement for professional training from a voice coach or similar, but there are four things that all researchers can very easily do without any extra training, so we don't just get our message across; we transform and mobilise our audiences.

4 points to transform your next talk so you transform your audience

No matter how terrified and unconfident you may feel, it is possible with a few tips and some practice, to present your research with real impact. Honing your presentation skills can help you make more of an impact on your academic peers as well as opening up opportunities for non-academic impact. Bad presentation skills can squander opportunities for impact and alienate the very people who might have benefited from our work.

Some researchers make talking to businesses and policy-makers look easy. The rest of us look on in awe, desperately wondering how we could create such succinct and relevant messages based on our research. Many of us conclude that it is “easy for people who do that sort of research”. However, most of these people started in a similar position to us; they just focused for a while on an aspect of their research that had the potential to be useful to that audience, and spent some time thinking about how they could communicate it powerfully.

Researchers have to do public speaking on a regular basis, but most of us are never given any proper training. There is no replacement for professional training from a voice coach or similar, but there are four things that all researchers can very easily do without any extra training, so we don't just get our message across; we transform and mobilise our audiences.

1. Have purpose

The first minute of your talk is make or break time. Based on what you say in your first minute, your audience could either be hanging on your every word, or pretty much dismiss everything you say in your whole talk. To engage your audience, there are just three things you need to do in your first minute:

Establish your purpose and the benefits your audience will get from listening to you: most of us know that we need to start a talk with our aims. I’m suggesting you should just have one single purpose that people can instantly understand and remember, and very quickly explain the tangible benefits that your audience will get as a result of achieving this purpose (even if those benefits are just learning something new). Finally, put yourself in the shoes of your audience and ask yourself why your purpose and the benefits you’ve identified, are likely to be important to them. Then actually explain why the benefits of listening to your talk are so important to your audience

Explain who you are and why your audience should listen to you: you don't have to be the world expert in your topic, but there must be some reason you are talking and not some random stranger picked off the street. What sets you apart from that random stranger? What credentials do you have? Why are you passionate about this topic? There is a fine line between establishing credibility and boasting, and you need to be careful not to alienate your audience by giving them your CV. However, there is good evidence to show that audiences are more likely to listen and learn from speakers that they deem credible, so it is important to establish this in the first minute of your talk

Sign-post what is coming next: people like to

know where they stand. You shouldn’t spend much more than a sentence doing this (don’t spend half of your talk going through your plan and explaining what you’re going to do). Just explain the key sections or steps you will go through to reach your purpose, so your audience feels able to relax into what is about to happen

a)

b)

c)

2. Connect

The best speakers empathise with their audiences, and their audiences identify with them. Opening a channel of empathy with a stranger can be a huge challenge; doing this with a room full of people you don't know is much harder. However, there are four quite straightforward things you can do to establish empathy with any audience:

Know your audience: do your research so you know who is going to be in the audience and why they have come. Be aware that there may be quite different segments of your audience who are looking for different things from you. If you are not able to research your audience, then take some time before you speak to sit next to someone in the audience and find out why they are here and what they are hoping to get out of the event. You will have to assume that their answers are broadly representative of the rest of your audience, but at least you are not going in blind. Once you know something about your audience, you can adapt what you say in your opening minute to make sure you’ve explained the benefits in a way that makes it clear why these should be important for this particular audience

Use powerful stories: we all know the power of stories to convey complex concepts in memorable ways, but not all stories have equal power. First, think of a few stories that are relevant to the one single purpose you identified in your first minute. They may be directly relevant or they may be a metaphor that you feel sums up your purpose powerfully. Personal stories help open a channel of empathy, showing that despite being up on stage you are just a person with weaknesses and passions just like them. Stories that demonstrate some degree of vulnerability, show that you trust the listener, and they are then more likely to warm to you and trust you themselves. If you can, try and include something unexpected in your story, to catch your audience’s attention, help them remember your story and make it more likely that they subsequently share the story with others. If you can paint a visual image with your story, whether in the mind’s eye or through pictures, your audience is more likely to be able to recall your story, and if the image

a)

b)

effectively illustrates your story, it will add real impact to what you are saying. Finally, engage to some extent with your audience’s feelings. This doesn’t need to be anything particularly dramatic, but stories that rouse some sort of emotion are more likely to stick than stories that leave your audience cold. If your story is strongly linked to the core purpose of your talk, then by remembering your story, your audience will remember your purpose, and from there, much of the content of your talk.

Ask “you-focused” questions: asking your audience directly to put themselves in your shoes can be a powerful way of establishing a channel of empathy with them. This may be difficult for many research-based talks, but with a bit of imagination, it may be possible. For example, “What would you do if…” or “What would you think if I told you…”

Use empathetic body language: it is possible to become a more empathetic speaker simply by making your body language more open and approachable. Consider choosing clothes that do not emphasise any differences between you and your audience (for example I often remove my suit jacket when training PhD students), avoid closing your body language, and adopt a positive and energized posture that shows your audience that you are putting in effort and really value them. You will often discover that your audience starts to mirror the emotions you are projecting through your body language, and will start to feel more open, trusting, interested, and energized by your talk.

c)

d)

3. Be authoritative and passionate

A lot of people avoid looking authoritative for fear of looking intimidating, but these are two very different things. Someone who is genuinely authoritative will typically embody a quiet confidence that does not need to boast or intimidate. Similarly, many people avoid being too passionate for fear of sounding like a salesperson or politician. Someone who is genuinely passionate about their subject however, will typically exude their passion without even trying and their audience will find their enthusiasm infectious.

There are 3 very simple things any speaker can do to demonstrate authority and passion:

Be aware of your feet: look at yourself consciously next time you give a talk, and see what your feet are doing. Some people pace; others step backwards and forward as they speak. Some people sway; others do a bit of a dance as they speak. All of them do it subconsciously and without realizing it, have a subconscious impact on their audience. As we move around, we are likely to distract our audience from what we’re saying, look less confident and create a sense that our words are insubstantial. On the other hand, speakers who have their feet firmly on the ground in one place are perceived to be focused, confident and substantial. This doesn’t mean you have to stand like a statue, but you need to use movement strategically. Choose a “home” position where you can introduce your talk and your core purpose (usually this is somewhere fairly central). Then have a number of “stations” around the stage (for example to the left and right of your screen) where you can move between points, to keep your audience’s interest and make clearer distinctions between points. Then at the end, return to your “home” position to make your conclusions and fulfill the purpose you set out to achieve.

Be aware of your hands: what you do with your hands can be similarly distracting and undermining if you are not aware of them. Putting your hands in your pockets may suggest a level of informality that makes it look like you’re not serious. Clasping them behind your back may make you look suspicious, like you’re hiding something. So what do you do with your hands? Simply clasping them in front of you is a safe bet if you’re nervous, but you will probably look nervous as a result. Using lots of flamboyant hand gestures may be very distracting for your audience. Draw a TV shaped rectangle in front of you, and keep all hand gestures within that rectangle. Avoid any kind of aggressive gesture, such as pointing, preferring a small number of open and inviting hand gestures. Now, your hands aren’t ever going down to your sides and drawing people’s attention away from your face; all of your gestures are bringing people’s eyes back to your face and your message. By using confident but muted gestures, you look credible, in control and confident, and can use your hands to add emphasis to your points and convey your passion.

a)

b)

Use emphasis to make every word and sentence count: if you’re going to say something, make it count. Make every single word count. If you find yourself trailing off, mumbling or skipping over words or sentences because they are not important, don’t say those words. Cut out the unnecessary words and sentences and then speak every single word in every sentence with equal conviction. Now, once you’ve learned to make every single word of every single sentence in your talk really count, consider how to put emphasis on the key points of each and every sentence, to demonstrate to your audience why it matters. You may want to use pace, slowing down and spelling out key points, or pausing before or after a key point, allowing it to sink in. You could use volume (sparingly) or vary your tone of voice more than you naturally would in conversation. Many researchers object at this point because it all starts to feel a bit fake. The last thing we want is for our audience to think we are insincere. However, most audiences expect people to speak slightly differently when they are on stage than they do in conversation, just as your family expects you to speak differently to them than you do to your colleagues at work. Your audience is far more likely to appreciate your more interesting and engaging style than it is to complain that you didn’t sound exactly like that when they spoke to you in the break.

c)

4. Keep it simple

The most common mistake that researchers make when presenting is to make their talk too complicated. Most of us can be forgiven for falling into this trap because our research is usually by definition fairly complex. However, the most successful communicators have spent time thinking how they can communicate their complex research in a way that is deceptively simple, and they will do so around a single key message, which they make as memorable as possible:

Find a single memorable message linked to the core purpose you identified in the first minute (in some cases it will be the same thing)

Present your key message early and revisit it from many different angles: if it is not presented during the first minute, then it should be presented in the first section of your talk. Then revisit it from different angles throughout your presentation, using metaphors, stories and images where you can, to make your point stick in people’s memories.

Link all your subsequent points back to your key message: having a single key message doesn’t mean you can only speak about one thing in your talk. However, it is important to remember that most people will only remember a fraction of your talk, and you have put in effort already to make sure that they remember the most important point. If you then clearly link each of your subsequent points back to your key message, then your audience is much more likely to remember these points when they recall the key point. Rather than having to remember many different stories and plot-lines, they only have to remember a single story and plot-line that logically flows from the memorable story or image you used to introduce your talk.

a)

b)

c)

Click this image to view presentation tips and fails as quoted from other professionals

Discovering that your research has commercial value is a mixed blessing for many researchers. Many researchers who come up with valuable Intellectual Property (IP) as a result of their work feel overwhelmed by the options they are presented with. Not wanting to abandon academia for business, many researchers do very little with the opportunities that arise, and as a result squander the chance to generate impacts from their work. However, you don’t have to change careers to exploit your IP. There are three ways to get as much impact as possible from your ideas, without having to give up your day job. We spoke to Stephen Oyston, Business Development Manager for N8 AgriFood at the University of York to find out more.

He explained that there are several ways to commercialize your ideas or “intellectual property” (IP) to realise impact from research. Each one has it up and downsides and the decision to go down one path over another will depend on the nature of your ideas, your institution, your personality and the level of commitment you are comfortable with. In all cases you should talk to your Technology Transfer Office (TTO) to assess the commercial opportunities of your IP and look at the potential commercialization mechanisms available to you. This will involve looking at potential applications and users of your IP, developing a commercialization plan and taking some initial steps.

The three typical routes available are:

Targeting a dream partner who can take your ideas to scale: this option takes a little bit more work, but not a lot. The problem of licensing your ideas to anyone who is willing to pay for the privilege (the non-exclusive license in the point above) is that these companies may not have the capability to develop your ideas to their potential. Even if they are capable of developing your ideas, they may have a different timescale to you and have quite different ideas about the sorts of impacts they want to see from your IP. Instead, consider working with your TTO to find a dream partner who shares your passion and priorities, and has the capabilities to develop your ideas in ways that will give you the impacts you most want to see. If you want to retain the right to develop your IP yourself in future, you need to go for a sole licence. A sole licence enables you to target a single organization you would like to develop your ideas, and you both have the right to use the IP. An exclusive licence allows the licensee to develop the IP in the confidence that no one else can access the IP. This can strengthen a research collaboration with your dream partner but caution is required. You will need to ensure you have chosen the most capable organisation to realise the potential of the IP.

Spin out companies are the hardest work, but if you are prepared to invest some time in the beginning, your TTO can help you put a team in place to run the business for you, so you don’t have to quit the day job. You may be able to set up as a not-for-profit company enabling you to invest profits in charitable work linked to your research. The spin out route gives you the greatest amount of control over realising the impacts you want to see from your research. However, many businesses need to raise capital before they can launch, which may expose your personal finances to risk if you take loans, or compromise your control over the company if you bring in investors. If you go down this route, you will need to work closely with your TTO to develop your ideas, as your institution will have a vested interest.

2.

3.

However busy you are, it is worth spending time negotiating the right deal if you want to commercialise your IP. Third parties and potential investors may have quite different motivations to you, so it is essential to have a really clear vision of the impacts you want to see arising from commercialisation before you go into any negotiation with commercial partners. Flexibility is necessary in any negotiation, but your TTO can help you get a deal that works for business, impact and your time.

Making your ideas available for others to use on licence: many academics worry that if they negotiate with companies, their best ideas may get bought up and then shelved by corporations that want to protect their existing products from your new ideas. The good news is that you don’t have to give up the rights to use your work if you grant them a non-exclusive licence. With this arrangement, you can license your IP to several different companies, and increase the likelihood that one of them manages to bring your ideas to market. Be careful though; if a company asks you to assign your IP to them, talk to your TTO and look at your options, or you may lose all rights over your IP. Your TTO will deal with the contracts. Then a third party pursues your impact, with minimal effort from you. Easy.

1.