Chapter 15

Empathic Leadership for impact

What do you want from leaders in your university? I have spent my career searching for people I can respect as leaders and being let down by the people I followed. Eventually I realised that I could be the leader I was seeking. Instead of looking to my university hierarchy or finding a new job with leaders I could get behind, I asked what I was looking for in a leader, and realised that I could provide many of these things for myself. So I will ask you again, what exactly do you want from your leaders?

My answer was something like this: I want a safe, protected space in which I have the time and resources to achieve impact alongside my research and teaching; I want someone who can inspire and mentor me, guiding me through difficult decisions and giving me constructive feedback without judgement when I’m falling short; I want someone who has a vision I can get behind, so we can achieve shared goals together; and I want someone who understands me and appreciates my strengths.

But how can you create all of those things for yourself? Well, by following the approaches I’ve outlined already in this book, I discovered that it was possible to create writing collaborations and apply for funding with people I trusted and liked from anywhere in the world. Together we were able to create our own writing and project cultures that gave us all a safe space in which to think and do our best work. I sought out my own mentors, one for each aspect of my career and life in which I wanted to develop. I clarified my own vision and sought out other like-minded people with whom to collaborate who shared that vision. Working with these people, I felt valued and appreciated, and I was given grace when I fell short of their expectations. Ultimately, I realised that I didn’t need the external validation of a leader who valued me, to believe that I had value.

As I provided myself with the leadership I craved, I started to discover others gravitating towards me as a leader, despite the fact that I had no position of authority from which to lead. It seems that there is something about the quiet confidence of someone who is pursuing a clear vision that draws others to them. I had learned this lesson early in my career from Ana Attlee, when I discovered that despite “only” being a PhD student, she was the only person in the centre I was supposed to be leading that anyone wanted to follow. In the years during which she has mentored me since then, she has enabled me to discover and start cultivating a source of power that animates all the leaders I have ever respected: empathy. It is a quality I have repeatedly come back to in this book, and now I’d like to explore it in a little more detail as a crucial aspect of effective leadership, whether that leadership is formally recognised or not.

The power of empathy

Empathy is the ability to sense another person’s emotions and imagine or feel what they might be thinking or feeling. It is feeling with, rather than feeling for someone. Sympathy looks into the mess someone has got themselves tangled up in and tells them how sorry they feel for them. Empathy gets into the mess with them and just sits there, understanding what it feels like to be in that tangle. The person who gives empathy doesn’t actually get tangled up in the mess themselves, because if you are tangled up yourself and in similar trouble, you are not in a good position to help if it is required. They do not immediately rush to untangle the mess and risk making things worse, because they first want to fully understand what has happened. They suspend judgement, recognising in that moment as they put themselves in the shoes of the other person, that given the same set of circumstances, they might be in the same mess themselves. Ultimately, empathy offers support that is adapted to the context, thoughts and feelings of the person in need.

There is, however, a dark side to empathy. There is a real danger that we feel so deeply for the other person that we become overwhelmed, stressed and unhappy about all the unmet needs we see and feel around us. Empathy requires psychological boundaries. This includes the self-control of containing your own emotions so they don’t “leak out” in an inappropriate attempt to sympathise (“I know how you feel – something even worse happened to me a few years ago…”). It also includes protective boundaries that enable you to keep your own identity and value in sight while you temporarily step into the reality of another person’s situation. Empathy with boundaries still reaches out with feeling, but in a measured and safe way. I lower my barriers enough to take in what it feels like to be the other person, but there is an inner wall that protects my inner self, so I cannot be overwhelmed by what I find when I reach out to the other person.

This inner barrier also enables the empathic leader to respond more effectively to criticism. Many of us instinctively throw up strong protective walls as soon as people start to criticise us, preventing us truly listening to the complaint or being able to learn from valid criticism. In contrast, the empathic leader takes a step into the reality of the complainant to see and feel the pain that has led to their criticism. Now, from the other person’s perspective, it is possible to truly see what they mean, and you can decide whether or not you agree with their criticism and decide on a course of action. Now, you step over the foundations of the strong outer wall you might instinctively have started to build around you, into the reality of the person criticising you, in the knowledge that you can retreat within a secure inner wall that remains intact around your identity and value. When you listen to the complaint, you may discover you have made a dreadful mistake, but you still know who you are and know your value, and so it becomes possible to admit and apologise for mistakes, and learn from them.

As such, empathic leadership is rooted in self-knowledge, self-compassion and authenticity. And these are some of the most powerful leadership qualities anyone can possess.

The power of empathic leaders

Empathic leaders have been popularly characterised as weak; too nice to make hard decisions. If misunderstood, empathy may be used as an excuse for being a “soft touch”, or lead to flip-flopping of opinions and decisions to suit those who shout loudest. If practised deeply, however, empathy can be a source of power and resilience. It can enable leaders to work through some of the toughest decisions to achieve global impacts. I have spent twenty years studying how ideas change the world, from humanitarian aid to product design, and again and again, I have discovered empathic leaders behind these world-changing ideas. It is empathy that enables researchers to identify challenges from the perspective of those who are in need. It is empathy that animates the conversations that lead to the ideas that actually meet those needs. It is empathy that drives the determination to try again and again when the first ideas don’t work, because you feel that need so deeply, you will do anything to meet it.

If the idea of the empathic leader still feels like a contradiction in terms, then try an experiment. Ask yourself which of the following words you typically associate with leaders:

-

Confident

-

Decisive

-

Authoritative

-

Powerful

-

Directing

-

In control

-

Self-sufficient

-

Expert

-

Demanding

-

Intimidating

While these approaches are associated with the leadership style of many high-profile leaders, they only represent one particular style of leadership, which can be described as authoritative, autocratic or top-down leadership.

Now, picture a leader from work and a leader from outside work, who has inspired you. List their characteristics. Most people come up with very different lists of words.

These people are leaders too. However, instead of directing others, they lead in a more participatory or democratic style, coaching, supporting or delegating to others. The way they do this is through empathy. To nurture or support colleagues, you have to know their strengths, weaknesses and desires – you need to put yourself in their shoes. To coach colleagues you need to know their goals and create a structured and accountable space in which they can find ways to meet their own goals. To delegate effectively, you need to know who has the capability and capacity, who needs to be given a break and who needs to be stretched – you need to know your team. People will follow an authoritative leader who directs them – to a point. People seek out and want to follow empathic leaders.

Part of the problem in developing an impact culture is that society has tended to respect and reward authoritative leaders who lack empathy. Those who lead “from the front” tend to cling to hierarchical or social power that gives them respect as the boss or part of an elite. These forms of power are rarely inclusive, lasting or motivational, though they can deliver short-term results in some contexts.

Another part of the problem is that it can be difficult to lead “from behind” in a system that is led from the top down through hierarchies and administrative processes that have the power to neutralise daring leadership. Most university systems are set up to prioritise research or teaching, not impact. As a result, even the most passionate advocates for impact are forced to make compromises. For example, we might tell our staff that we want them to generate impact from their research, but when they spend too much time in their unremunerated charity role or start-up that has yet to turn a profit, we tell them they have to take a pay cut and work on a fractional contract. We might want to coproduce research through intensive engagement with stakeholder organisations. But many UK research funders only pay 80% of the costs, and while universities receive overheads that help absorb these costs, they have to find the additional 20% to pay stakeholders for their involvement. As a result, significant paid roles for stakeholders in research are rarely approved by university decision-makers. I will discuss this issue further in Chapter 18.

If you want to be an empathic leader, you may need to lead despite the system, and sometimes against the system. To do this, you need a deeper source of power than the hierarchies that constrain you. It is this power that makes empathic leaders “natural leaders” that people can’t help being drawn to. No matter where you sit in your organisational or social hierarchy, the personal and transpersonal power that underpins empathic leadership has the ability to inspire others to do great things.

Three pillars

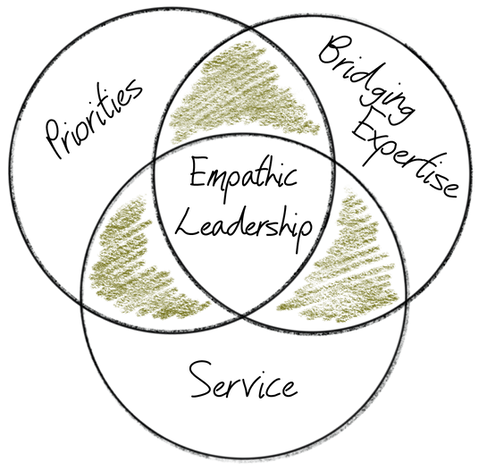

The three pillars of empathic leadership are: purpose, bridging expertise and service. Empathic leaders are experts in people, and experts at channelling and connecting what those people have to give. Rather than building enough specialist expertise to make the right decision every time, empathic leaders have the ability to create bridges between different sources of knowledge, the humility to listen without having to be right, and the sensitivity to balance moral arguments alongside potentially conflicting lines of evidence. Rather than only serving their own interests, empathic leaders follow a deeper purpose and meet their own needs as they meet the needs of others.

Understanding your purpose is the first pillar of empathic leadership, because the first step to knowing others is to know yourself. In Chapter 12, you drew your purpose forest to identify how different parts of your identity (trees) are rooted in in your values (tree roots), before systematically identifying the most important (deep) roots and (tall) trees. However, trees need time to mature, and we often find that we spend far less time than we want in the parts of our identity that are most important to us. When these are linked to deeply rooted values, this stunting is often a source of significant anxiety or suffering. The final step of the exercise was therefore to identify priorities that emerged from the tallest trees that were fed by the deepest roots, to start finding practical ways of rediscovering your identity, enacting your values and achieving your purpose. This purpose is the basis for the vision of empathic leaders. Because it is so deeply rooted, your purpose stands firm in the storms of changing circumstance, criticism and failure, providing a source of inspiration that enables you to persevere with your vision.

.png)

The second pillar of empathic leadership is bridging expertise. Expertise has little to do with qualifications or recognition; it is something you get with practice. You can be an expert without being able to read or write, but no matter how well you read and write, you will never be an expert at something you don’t practise. Most of the experts we recognise in society are specialists with deep and narrow expertise. The alternative to ever-sharpening the point of your expertise, however, is to become the person who joins the dots to gain new insights and see the bigger picture: a bridging expert. By channelling the expertise of others in this way, you have the power to integrate evidence from multiple sources to make better decisions than the often-blinkered perspectives of specialists. The best bridging experts draw from many diverse sources. Rather than being fooled by the prestige of the source, you now value and look critically at knowledge from all available sources, and piece together balanced decisions in ways that give you a more nuanced understanding than any specialist is likely to have. Respecting knowledge from some sources is easier than others, and often requires humility. We all respect the findings of a good systematic review of peer-reviewed evidence, but there are now many methods for integrating and critically analysing the knowledge of publics and stakeholders. Moreover, my colleagues and I have published evidence that decisions based on participatory processes are often more effective and durable than decisions based on expert knowledge from researchers alone. Some of the most effective bridging experts I have met in my career span multiple networks of people who do not typically interact with each other. In my own career, I started by creating bridges between researchers and environmental charities in the field I was working in, before building networks with people in different policy worlds. Now I am building my international policy networks and corporate networks, and it all takes time. But this is a form of expertise, and becoming an expert in anything takes time. If you want to build bridging expertise, you will need to seek out and add value to groups of people who might naturally be suspicious of your motives. You will need to identify key individuals and organisations that are centrally positioned within the networks you want to work with, and consistently reach out and help them, staying in touch and adding value, whether or not you have a funded project or team in place to help you.

The third pillar of empathic leadership is service. Many leaders start with their own needs, to set up their spin-out company or become an adviser to the United Nations, to change the world their way. Very often, just beneath the surface of these apparently altruistic visions is a deep need for validation and belonging, which is often the real drive behind their leadership. Because the empathic leader is pursuing a sense of purpose that has emerged from a deep understanding of their own identity and values, they are psychologically free to ask genuinely what the world needs, rather than focussing subconsciously on what they need. If you start from this place, you are more likely to tap into to the greatest needs and opportunities of your time. Or, more simply, you might just stumble across important needs and opportunities on your own doorstep that everyone else overlooked. One of the reasons you will see opportunities and needs that others miss is because you look differently at the world. Instead of looking from the outside in, you look from the inside out. You take the empathic step into what an opportunity or need looks like from the perspective of those closest to it. This deeper looking not only identifies opportunities and needs, it identifies others who want to address the issue, giving you allies and a team. You are not alone anymore; you are working with others who have complementary ideas and skills, and may have additional capacity and resources to throw at the problems you want to help solve. As a result, you coproduce impacts with those you seek to serve and with others who have the same goal as you, and you achieve impacts that meet real, felt need, faster and more effectively than would otherwise be possible.

Based on these three pillars, there are three questions you can ask yourself, if you want to become a more empathic leader:

-

Based on your purpose and your most important priorities (see your purpose forest in Chapter 13), what change(s) do you want to see, and how could this benefit others?

-

Who could you connect with to access the knowledge, skills and resources necessary to achieve the change you want to see, and what benefits will they get from engaging with you?

-

What needs can you meet as you pursue change with these people, and how might these needs influence the change you want to see?

The radical resilience of empathic leaders

The worth of a great leader is shown most clearly in adversity, and the types of power wielded by empathic leaders gives them remarkable levels of resilience when things go wrong. Conventional wisdom suggests that leaders who prepare for the widest range of threats to their leadership and build strength strategically in these areas are most likely to survive adversity. However, no leader is able to anticipate every potential threat, and resilience strategies based on strength tend to fail because they create strong but brittle and blinkered leaders who are blind to unexpected threats until it is too late. On the other hand, empathic leaders are necessarily vulnerable, acknowledging their weaknesses and limitations, drawing on the expertise of others and open about the values they care most deeply about.

However, there is a counterintuitive resilience at the heart of this vulnerability. Empathic leaders are more likely to possess psychological foundations of personal resilience. For example, as an empathic leader, your humility enables you to ask for help, rather than waiting till it is too late. You are more likely to practise critical awareness and mindfulness, so you tackle rather than avoid problems as they arise. You are less likely to feel isolated at the top or hopeless when things go wrong, because you retain strong social bonds and a connection to a higher meaning or purpose that you can draw from in times of crisis. You build social capital, which puts more human and other resources at your disposal than other leaders, and you use these resources more effectively because your bridging expertise gives you flexible ways of dealing with challenges from multiple perspectives.

These characteristics enable empathic leaders to move beyond strategies based on strength, to adaptively practise three radically different and more effective forms of resilience. First, in some cases, disaster cannot be avoided, so, as an empathic leader, you focus on recovering from disaster and enabling your team to bounce back as quickly and as fully as possible, with minimal scarring. For example, in response to the Coronavirus pandemic, many companies went into hibernation, using furlough schemes to retain their staff so they could restart operations as soon as restrictions were eased.

Second, if it is not possible to bounce back, then you may adapt, enabling your team or organisation to change what it does so you can protect your core mission and still achieve the things that are most important. For example, other companies responded to the pandemic by adapting their operations (most training companies like Fast Track Impact moved all their trainings online). As part of the adaptation we made the trainings more interactive than ever before, gave participants an edited recording of the session, added personal follow-up for all participants a month after the session to see how they were getting on and help as necessary, and in addition to posting everyone a hard copy of the book the training was based on, we gave them a PDF copy to use during the session.

Third, if that is not possible, then the empathic leader can move to transformation. In this case, you lead the transformation of your team or organisation into something that is structured or functions in new ways, delivering new outputs that are valued as much or more than what the organisation was previously known for. In doing this, you reframe your challenges and find more disruptive ways of achieving things that are completely different and yet valued even more than the old ways of doing things and the outcomes they produced. For example, instead of adapting to the pandemic to offer the same service in new ways, some companies transformed their entire business model to offer different products and services. For example, The Second City improvisation theatre switched from performing to offering online improvisation comedy courses. I know of many public engagement professionals who have been thinking along similar lines. Instead of trying to adapt a science festival to run online, they are surveying their community to find out what they actually need, and using their festival resources to run online courses or helping turn their local soup kitchen into a “drive through” pantry bag pick up or home delivery service.

Tools for empathic leaders

If you want to develop your empathic leadership skills, you need tools that can enable you to connect deeply with those you seek to serve, so you can genuinely put yourself in their shoes. I have covered many of these in more depth in The Research Impact Handbook and on my website, so I will summarise two categories of tools that I think are particularly important here, and let you research these in greater depth yourself.

1. Deliberation tools

First there is a large body of work on participatory and deliberative methods that are essential for any empathic leader to be skilled in. The reason that these tools are so important is that they enable you to listen deeply to everyone you serve, not just those who shout loudest. You are trying to move beyond engagement to active participation of your colleagues and stakeholders in your work. And if possible, you are trying to move beyond just enabling participation to facilitate deliberation.

Deliberation is a widely misunderstood concept; it is much more than just discussion. Based on the literature, deliberation should in theory involve four steps:

-

Searching for and acquiring information, gaining knowledge (by learning), and forming reasoned opinions;

-

Expressing logical and reasoned opinions (rather than exerting power or coercion) through dialogue;

-

Identifying and critically evaluating options that might address a problem; and

-

Integrating insights from deliberation to determine a preferred option, which is well informed and reasoned.

In short, deliberation is as much about listening and learning from others as it is about engaging in reasoned debate yourself. How to enable this kind of engagement between colleagues is the real challenge.

Some of my own empirical research (published in a paper led by Joris de Vente in 2018) shows the importance of strong facilitation and the use of structured elicitation techniques if you want to enhance learning and trust and achieve beneficial outcomes. For example, instead of opening a group discussion with an open question, you might ask everyone to write as many answers as they can think of on a piece of paper before inviting everyone to do a “round robin”, stating their best idea, moving to another idea on their list if someone else says what they were going to say first, and giving people the option to pass if they prefer not to say anything. Alternatively, you might write the question on a flip chart, give everyone three sticky notes and ask them to write their three best ideas on the sticky notes, bringing them to the front when they are ready and clustering similar ideas together. I do this online with Google Jamboard, telling everyone they can have one sticky note of each colour to provide up to five ideas (there are five colours of sticky note). In each of these simple methods, I am able to hear ideas from everyone in the group in around five to ten minutes, compared to a half-hour discussion that would probably have been dominated by a minority of the group members. Having time to think before they write, and see other people’s ideas before they move into discussion, increases the likelihood that people are doing their best thinking, compared to trying to think in parallel with listening to a discussion and only being able to respond to the most recent idea that has been expressed. Both of these techniques also force people to listen to everyone else in the group before they start discussing, as everyone takes their turn in the round robin, or as people read each other’s sticky notes in order to cluster similar ideas together. Both techniques enable people to take time to form their ideas coherently before they speak. It is the concision required to speak your idea in a single sentence or less than a minute (round robin gives everyone approximately the same airtime) or write it on a sticky note (I often give people felt tip pens or tell them to write their idea in 12 words or less, and Google Jamboard has a fairly short character limit), that forces people to organise their thoughts before presenting them.

Deliberation must then create spaces in which people can discuss those ideas with each other, evaluating what is said by others to form reasoned insights or decisions. Although it sounds a little heavy-handed, ground rules, if they are done well, can be an effective way of doing this. I like to start by referencing Nancy Kline’s “thinking environment”, based on her book, Time to Think. It is worth reading her book or looking up her ten components of a good thinking environment. In summary, her proposition is that we do our best thinking when we are listened to deeply, and so your task, if you want to facilitate true deliberation, is to create the kind of considered pace, equal turn-taking and respectful attention that enables people to listen first, and then both think and express themselves without fear of interruption or recrimination. If your group agrees that they want to do some of their best thinking together, and that this is the basis of a good thinking environment, it is possible to lay down some simple rules at the outset around the kind of language we use, how we show we are listening to each other, the importance of not interrupting or changing the subject before a person has fully developed their ideas etc. This can be done in less than a minute.

The secret power of ground rules lies in the social contract you create with the group. Whether you are laying the foundation for the first and all subsequent meetings at the start of a new project or you are starting a teleconference, you must ask everyone if they agree and want to remove or add any rules to the list. Only move on once you have paused long enough to ensure you have the agreement of the group. Now, if someone starts to break the rules, you can remind them of the conversation you had at the start of the meeting, and because this was a social contract, effectively signed by everyone in the group, the peer-pressure to conform to the rules is powerful enough that most people will comply, even if they are significantly more powerful than you and they would rather not comply. In the worst-case scenario, for a repeat offender, you can cite the agreement you all made at the outset as the reason you will have to take a short break and escort them from the room, or disconnect them from the call. Scary as that may sound, you will do so on behalf of the group, and can make this clear, giving you both the power and authority to take the necessary action to maintain a safe space for the group.

It is easier to manage discussion in smaller groups, so consider breaking the group into small groups and running a carousel activity where you create a small number of discussion groups (say one per corner of the room) and tell people to start at the topic they are most interested in, rotating groups with a decreasing amount of time per group, until you ask them to visit their original group to read what was added by other groups over the break or as they return to their seats. When doing this online, I ask people to tell me the topic they are most interested in via the chat function over a break, and I create the groups before they come back from their break. Then I run a second shorter rotation, where I randomly allocate people to groups (explaining that some people will get to continue discussing their favourite topic with a new group of people). When doing this online, each group has their own Google doc in which everyone discussing can write their own points. Some people write without speaking and that’s fine.

Alternatively, instead of letting people choose the topic that they are most interested in, you can choose who goes where on the basis of the group dynamic. For example, you might place people who you think will be difficult to manage in separate groups, or put them all in one group and get the most experienced facilitator in your group to manage them.

To avoid a power-play when we choose which topics to prioritise for discussion, I do a sticky dot prioritisation where everyone gets the same number of dots in their hand or virtually, which they can allocate to the full list of possible topics, which will often have come from a metaplan (the first sticky note exercise I described at the start of this section). You can do the same at the end of the process if you need to make a decision. A prioritisation exercise is more effective than voting because it is relatively anonymous when people are sticking dots on options in a room, and entirely anonymous online, so people can express their preferences without fear of later recrimination.

Alternatively, you can do a more sophisticated prioritisation using multicriteria evaluation, where you create a matrix with the options you are choosing between in columns, and the criteria against which you will make the decision in rows. For example, as a team you might be struggling to choose between three courses of action: create a prototype, make a video about the research you have done so far, or do more research. Instead of prioritising one of these actions straight away, you first discuss the reasons why you might in theory prioritise one action over another. For example, you might consider the extent to which the options will deliver impact, how inexpensive they are and whether you currently have the capacity in your group to perform each action. Now when people place their ten sticky dots on their preferred action, they have to say why they are prioritising that action by placing it in the relevant grid. I might prioritise the first option because it will deliver impact, placing six of my sticky dots on row one of option one; I think we should build a prototype because that will have most impact. However, I can now see that this will be expensive and we don’t have the skills in our group to do this, so if this isn’t possible, my second preference would be to make the video. I might therefore place my remaining four sticky dots on the video option, placing one dot in row one (impact), and two each in rows two and three (expense and skills); if we can’t build the prototype, we should make a video as it would still have some impact, it would be inexpensive compared to the prototype, and it is something we could do already as a group.

Multicriteria evaluation is not designed to get consensus. Getting everyone to agree is not the job of an empathic leader. Most attempts to get a single answer from a group arrive at a dysfunctional consensus where at least one person decides it isn’t worth pushing their point. Instead they say nothing and let the decision go ahead, or say what they think the rest of the group wants them to say. Either way, resentment can smoulder, leading to rifts in the group and later accusations that you didn’t give them their say or listen to their perspective. As a result, decisions may be constantly revisited, undermined or delegitimised by those who felt their perspective was not heard or given due weight. Multicriteria evaluation, on the other hand, makes each of the different perspectives explicit and enables everyone in the group to first discuss and then vote against these perspectives. As a result, it may become apparent that half of the group actually share the same perspective as the person who might otherwise have kept quiet, assuming that everyone shared the opinion of the most vocal or persuasive person in the group.

Now, as a leader you can open a much deeper channel of empathy with each of the different perspectives in your group, and the layers of values and beliefs that lie behind a seemingly simple decision. You will still have to make a decision, but you can now consider how you might ameliorate some of the negative consequences of that decision to make it a win-win for more members of the group. If nothing else, you are able to acknowledge the depth of compromise that some group members will have to make to live with the decision you make. The decision you make doesn’t have to match the arithmetic conclusion of the evaluation. As a group, the majority of people might have opted for doing more research, but if this is a decision about how to use funding that is specifically earmarked for impact, then after discussion you might decide that some of the funding could be used to send someone from the group to do some training. Everyone had assumed that they would have to employ a consultant to build the prototype, which would be far beyond the budget available. However, one of the team is now looking very excited about the prospect of learning these new skills, and if you can afford the training, then perhaps the majority of the group are now up for building the prototype. If not, then at least it is clear that the group agree a prototype would be the most impactful option, and you can apply for the funding to make this happen in the long-term, while using your current budget to do more research.

2. Coproduction tools

Finally, it is worth revisiting some of the planning tools I introduced in Chapter 11, to show you how these can be used to coproduce impact with your team and stakeholders. “Coproduction” is as misused a concept as deliberation, and usually equates to some form of consultation. Consulting your stakeholders to get approval for a course of action you want to take is very different to listening to the needs or aspirations of your stakeholders and offering to help them achieve their own goals. There is a very different power dynamic at the heart of coproduction, in which we are now serving the needs and interests of our stakeholders, who are in charge of the process. Even if we think we understand and are serving their needs, if the funding has come from our research and we are in charge of the budget, which also has to produce research outputs, then there will still be a power dynamic in which our stakeholders to some extent are serving us or the agendas of our funders. We are organising the process, so we get final say over who is involved and can veto courses of action that will compromise the quality of our research outputs. “Action research” and “practice-based arts” attempt to turn this power dynamic on its head and put stakeholders in the driving seat, but in my experience, it is rare to find truly coproductive work outside these traditions.

I will consider coproduction in greater depth and describe some examples that have inspired me in the penultimate chapter, but at this point I want to show you how some simple tools can enable you to take a more coproductive approach to your work. The starting place has to be a more systematic approach to identifying who might have a stake in your research, including nonhuman stakeholders, future generations and the marginalised and vulnerable. Without taking a systematic approach, you might fall into the same trap as those who have come before you and further marginalise a group who currently have no voice and are regularly excluded from decisions that affect them. Such groups are often “hard-to-reach”, but a stakeholder analysis enables you to both identify and empathise with these groups. Go back to Chapter 11 or search for my 3i’s approach to stakeholder analysis if you want more details on how to do this. Here I want to emphasise the empathic power of a good stakeholder analysis, and how this can enable you to coproduce research and impact.

The empathic step in a stakeholder analysis is researching, and beginning to understand, the needs, interests, opportunities and constraints of each group you think might share some of your interests. Doing this exercise alone or in your research group, you will often discover the limits of your knowledge, identifying groups that should in theory be relevant, but you are not quite sure what their interests would be. As a result, I like to do stakeholder analysis with a small number of key stakeholders who know the stakeholder landscape much better than I do. This means I don’t only learn about the interests of these groups; I learn about their sensitivities, words I should avoid when working with them, conflicts between them and other groups I need to be aware of, and hidden powers I was previously unaware of. Now I can take this to the next level by opening dialogue with more stakeholder groups directly, and when I reach out to them, I do so with empathy, based on their needs and interests.

The conversations you have with these stakeholders need to be in listening mode, trying to understand the goals and challenges each organisation faces, and as far as possible the context in which they are working. Depending on the group, you may need to be introduced by someone who is already known and trusted by the group, and where possible I would suggest you ask them to accompany you to your first meeting. It is important to realise that what you can understand from one meeting will only ever be a distorted fragment of their actual reality. Anthropologists might work with them for months or years to provide an ethnographic account in which they would still acknowledge their subjectivity and “positionality”. If you are successful, you will look back at your perception of the organisation and their context in years to come and be shocked at your own naivety. But this realisation should not stop you from trying to reach out and understand what it is like to be in their shoes. The secret is to be curious, and this is the superpower of every researcher. In the same way you are innately curious about your research, become more and more curious, and where it is not rude, keep asking “why” questions. When you finish, ask who else they think you should speak to, to understand more. Social scientists call this a “snowball sample”, and they continue interviewing until they hear no new ideas. This isn’t practical for most of us, but it is always useful to check if there are any particularly important people you need to speak to from the perspective of your stakeholders. Often successive people will point to the same person again and again, and this is a sign that you need to make time for at least one more conversation.

The final step is to make some kind of plan for your work together. The best starting point for a truly coproductive approach is to find out what plans your stakeholders already have. If you can help with their existing strategy or programme of work, then they will remain in charge and take most of the credit if things go well. You will be serving their interests, rather than diverting them into your agenda in the service of your research or funders. In some cases, there is an unmet need and nobody has a plan. Now you can play a facilitating role, but this should be neutral and focussed on meeting their needs rather than providing impact for your research. If possible, hire a local facilitator, who is independent enough to be trusted by the group, rather than facilitating this yourself. There are enough implicit power dynamics inherent in your title of Doctor or Professor, without you leading from the front. Done well, the needs and options identified will only intersect partially with your interests as a researcher. Your task then is to do what you can to connect people with others in your network who might be able to help with the issues that are beyond the scope of your project or expertise. Others in the group will have their own contacts. The group needs to self-organise, and you need to resist any attempt to make you chair of the steering group, if that’s what emerges from the process. If you are in the role of serving the community, you could even question being a member of such a group. Tools like logic models and theory of change may be useful at this point, but only if those leading the initiative find them useful, and not if the use of these tools ends up putting you back in the driver’s seat.

* * *

As we reach the end of this chapter, it is important to reflect on what actions are arising for you. Are there parts of your life in which you could be a better leader? What would more empathic leadership look like for you? Practically, what could you do that would enable you to connect with and express your deepest priorities and purpose in the way that you lead? How could you build your own bridging expertise? Who do you need to serve better?

Empathic leaders lead from behind. They are often not recognised and are rarely thanked for what they do. The satisfaction that arises from this approach lies primarily in what they see others being enabled to do as a result of their actions, what I have heard some people refer to as “second-hand glory”. The power in this type of leadership comes from the deep places rather than the high places in this world.